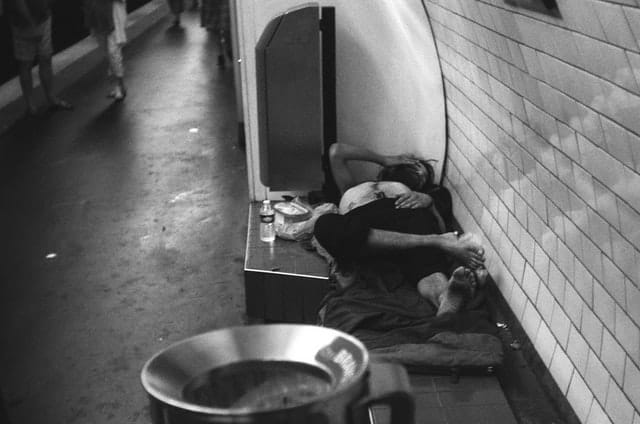

George Orwell is perhaps best known for his seminal works 1984 and Animal Farm. One of his lesser-known works that I’ve come to appreciate is Down and Out in Paris and London. The book is an examination of working-class poverty in 1929 Paris and London. It is true that George Orwell had a safety net. Just as Thoreau lived on Emerson’s property for free and often went back into Concord to either dine or do laundry while he toiled away writing Walden, Orwell always had the ability to contact his middle-class family for help if he did get into real trouble. Knowing that does, in a way, vitiate some of the desperation we read about.

That being said, the short chronicle, weighing in at just past 200 pages, is worth the read, if only to appreciate just how “first-world” our problems these days really are when so many of us have running water, indoor plumbing, and a bed to call our own.

For, when you are approaching poverty, you make one discovery which outweighs some of the others. You discover boredom and mean complications and the beginnings of hunger, but you also discover the great redeeming feature of poverty: the fact that it annihilates the future. (from Chapter III)

Obviously, there is a stoic positivity to this — who needs to worry about tomorrow? Focus on the daily. And yet, that annihilation of the future also implies a destruction of dreams and goals.

There’s a humorous moment in the book when I realized that immigration problems don’t just belong to our century. Orwell recounts a visit to the pawnshop:

And then, after all our trouble, the receiver at the pawnshop again refused the overcoats. He told me (one could see his French soul revelling in the pedantry of it) that I had not sufficient papers of identification; my carte d’identité was not enough, and I must show a passport or addressed envelopes. Boris had addressed envelopes by the score, but his carte d’identité was out of order (he never renewed it, so as to avoid the tax), so we could not pawn the overcoats in his name. (from Chapter VII, emphasis mine)

There’s also an unexpected insight into the life of waiters and service staff in Parisian hotels and restaurants, where Orwell has to turn for work as his money dwindles away to nothing. One would hope that hygiene and other practices recounted in the book have improved…but perhaps they are simply toned down rather than gone.

A good 65% of the book is dedicated to Paris — the rest to London. Perhaps the biggest surprise was how prepared the English were to accommodate the homeless through a series of government shelters. They were dreadful, but still offered room and board for a night.

In one of the final chapters Orwell reflects that: “The evil of poverty is not so much that it makes a man suffer as that it rots him physically and spiritually.” If the book inspires you to do anything, it may be to help people out of poverty, and the first world does have real and practical tools to do that, starting with sites like Kiva, which allows you to loan as little as $25 to people looking to improve their lives around the world through various endeavors and projects.

But perhaps the lasting lesson for me is that today, as in Orwell’s time, it is possible to live meanly, or even well, for not a lot of money. Reading about the darkness Orwell experienced makes you appreciate the City of Light that much more.

Photo by Lizgrin F on Unsplash

Did you enjoy this article? TAIP is 100% reader-supported through tipping. If you want to leave us a tip of any amount it would be highly appreciated. These tips help support our efforts to keep TAIP an ad-free environment. Just as at a cafe, the tips are split evenly among the team.